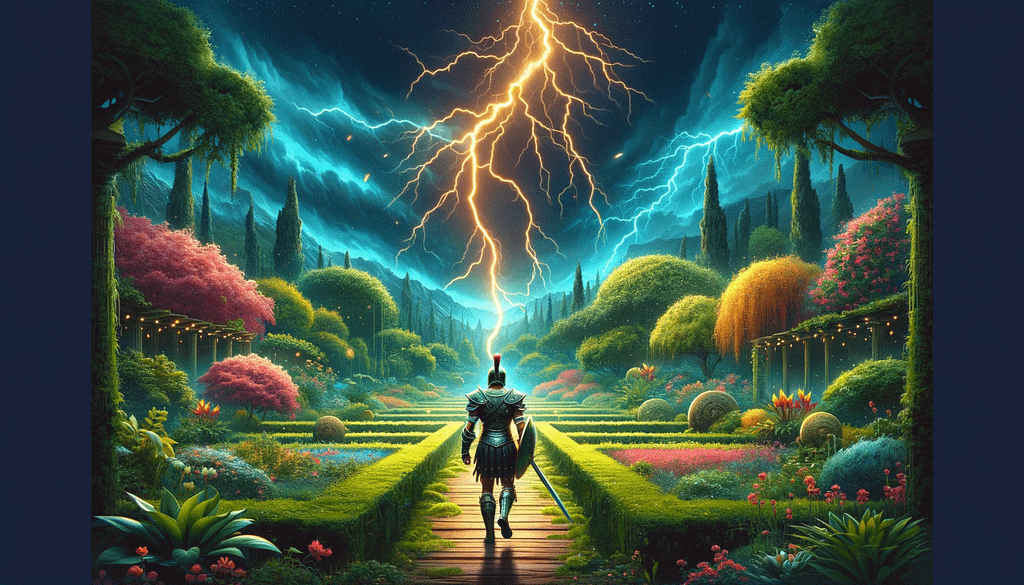

“It is better to be a warrior in a garden, than a gardener in a war.” — Miyamoto Musashi

In my journey to author “Undisruptable”, I considered areas of my life that were languishing at the top of the first curve. Inspired by the Spartan mantra, “The more you sweat in peace, the less you bleed in war.”, I focus on nurturing my relationships, continuous learning, and maintaining health.

My daily regimen includes rigorous strength and mobility training, a lifestyle shift from driving to cycling, zero alcohol and no caffeine post-noon, practising intermittent fasting, and adhering to a strict bedtime routine at 22:30. I aim to stand strong, agile, and healthy at the age of one hundred at least. When people see how I live, a common remark is, “What if you do all this work and you still get sick.” Immediately I think, “What if I don’t.” My rationale? No regrets, do everything to succeed and leave no stone unturned. This approach, inspired by previous guest on The Innovation Show , Daniel G. Amen, M.D., revolves around a proactive stance towards life, aiming to leave no stone unturned in the pursuit of healthspan and to avoid becoming a burden on my loved ones. Amidst life’s inherent chaos, adopting such measures can indeed skew the odds in our favour.

The wisdom in Miyamoto Musashi’s adage, “It is better to be a warrior in a garden, than a gardener in a war,” encapsulates the essence of this preparedness. This principle, explored in Musashi’s “The Book of Five Rings,” advocates for readiness in every facet of life, suggesting that strength and preparedness should be upheld even in tranquillity to avoid being caught off-guard in adversity.

This metaphor extends seamlessly into the business realm, symbolizing the necessity for resilience and adaptability in the face of unforeseen challenges. While human bodies are subject to ageing (programmed obsolescence), corporate bodies face the innovator’s dilemma, where timing the leap to a new business model is critical. By jumping to a new business curve too soon, you risk losing your best customers and you may be walking away from years of profit. Worse yet, you may put yourself in direct competition with yourself. However, if you stay the course too long, you may never get a chance to reinvent ahead of the necessity to do so.

However, as I discussed with Ian Morrison, author, futurist and former director of Institute for the Future, even the most prepared warriors fall victim to unpredictable forces. His insights into Pitney Bowes’ navigation through technological shifts and market uncertainties illustrate this point.

Bowes’ Woes

Even when you are a warrior in a garden, lightning might strike you down

“So much of life, it seems to me, is determined by pure randomness.” — Sidney Poitier

Decades ago, Pitney Bowes chairman George Harvey characterised the dilemma his company was facing. On one hand, he knew there was potential for a second curve to emerge in terms of technology substitution for the mail. He could see evidence in their business, and they had made provisions for it in terms of the business-to-business segment of communications investments in copiers, fax machines, dictaphone and voice messaging systems. He recognised that traditional business-to-business mail for large users in the United States, which Pitney Bowes had supported through both mail meters and production mail capacities, would not continue to be the most rapidly growing business segment.

Pitney Bowes leadership understood that new growth would come in services in the small business sector and the global market and from new definitions of mail. Similarly, on the business-to-home side, there were concerns within the organisation about the potential substitution of business-to-home mail. Information generated by both financial services (statements, bills, credit cards, etc.) and direct marketing could potentially shift over to electronic media once an infrastructure had been established in the household. But, as Harvey correctly ascertained, premature abandonment of first-curve businesses made no sense either strategically or financially in the short run. The uncertainty of the second curve was inherent, but it was also real, and Harvey brought a great deal of experience to his decision. He’d been in this movie before; he’d seen others’ premature attempts at bringing about the paperless office-but the paperless office never came to pass. One of the best things that ever happened to paper was the computer, enabling an explosion in many dimensions: desktop publishing, directories, and the use of paper as the interface.

In Pitney Bowes’s case, much of the thinking about the second curve came from the futures group, which was chaired by Harvey himself, but which included some of the young up-and-coming middle-to-senior managers, who viewed the company as their company for the twenty-first century and wanted to point out and help grow second-curve businesses inside Pitney Bowes.

Pitney Bowes had done everything right, they didn’t just scenario plan the Internet future, they understood it and they invested $325 million in R&D from 1990 to 1992. Moreover, they built leadership capability for the future with a futures group, spearheaded by top leadership. They even prepared this group to seamlessly pass to the new CEO of Pitney Bowes, Michael Critelli.

So how did it play out?

Ian tells us, that if you look at the stock price through the 90s, their stock quadrupled because they managed the first curve pretty well. They were throwing off a lot of cash. Mail continued to grow, and they continued to invest in newer technologies and services. They also maintained a strong balance sheet, which they leveraged with their financial services arm. What were the primary drivers of the mail business? Financial bills, statements, and direct marketing. Pitney Bowes clearly understood how these streams could migrate to e-commerce platforms. They carefully monitored shifts not only in the U. S. but globally.

Ian talked recently to Mike Critelli and asked what happened. In the end, it was a Black Swan event. Even though they had done about everything correctly, the 2008 recession wiped them out. Mike Critelli writes about it openly on his website. Before 2008, a reliable source of revenue was the solicitation of college-aged kids by banks for credit cards, on the first day of college. The banks did this routinely, but not in 2008 because they didn’t want the bad risk on their books in the 2008 recession.

Let’s revisit George Harvey’s prediction back in 1990. He was right. He correctly foresaw that premature abandonment of first-curve businesses made no sense either strategically or financially in the short run.

First-class mail in America grew continuously until 2007. By jumping to the second curve too early and moving all their chips to a new curve would have meant walking away from 17 years of profits.

Even with all the preparedness of this team, sustaining a postage meter business in a digital age is a tough ask. As Michael Critelli writes, “Market conditions change so rapidly today that 25–35% of all Fortune 500 companies disappear within any 10-year period. Many are acquired and others go out of business.”

Even when you are a warrior in a garden, lightning might strike you down, but I’d still rather be a warrior in a garden, than a gardener in a war.

Part 1 of a 2-part series on “The Second Curve: How to Command New Technologies, New Consumers and New Markets” with Ian Morrison is available here:

https://medium.com/media/17469979648a7bcebae014dc221a3af2/href

A Warrior in a Garden or Gardener in a War? was originally published in The Thursday Thought on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

The post A Warrior in a Garden or Gardener in a War? appeared first on The Innovation Show.