“Business men go down with their businesses because they like the old way so well they cannot bring themselves to change. One sees them all about — men who do not know that yesterday is past, and who woke up this morning with last year’s ideas.” — Henry Ford

[This week’s Thursday Thought is inspired by a custom Keynote I delivered for Enterprise Ireland’s Food Innovation Summit 2024.]

Just as a plough furrows a rut in the field, neurons in our brains create well-worn pathways that facilitate quick thinking and high performance. These neural shortcuts are crucial for efficiency, allowing us to respond rapidly to familiar situations and tasks. However, this efficiency comes with significant implications for innovation and change. Over time, these neural pathways become entrenched, much like the deep grooves in a field, making it challenging to deviate from established patterns. As a result, we can find ourselves stuck in the mental ruts we’ve created, hindering our ability to adapt to new ideas and innovate. This neural rigidity mirrors the organisational challenges faced by companies, where adherence to established processes can stifle flexibility and creativity. We often overlook that every organisation once began as a startup, fumbling and furrowing until it found a repeatable revenue-generating rut.

This week’s Thursday Thought illustrates the double-edged sword of innovation. While it can propel an organisation to new heights, becoming too attached to a single method or product can hinder further growth and adaptability. I hope this story serves as a cautionary tale about the need for continuous evolution and the perils of success in a rapidly changing market. Managers must balance the pursuit of efficiency (exploitation) with a commitment to continuous innovation (exploration), ensuring that their organisations can swiftly adapt to new demands and technological advancements. An over-investment in the present can limit one’s future.

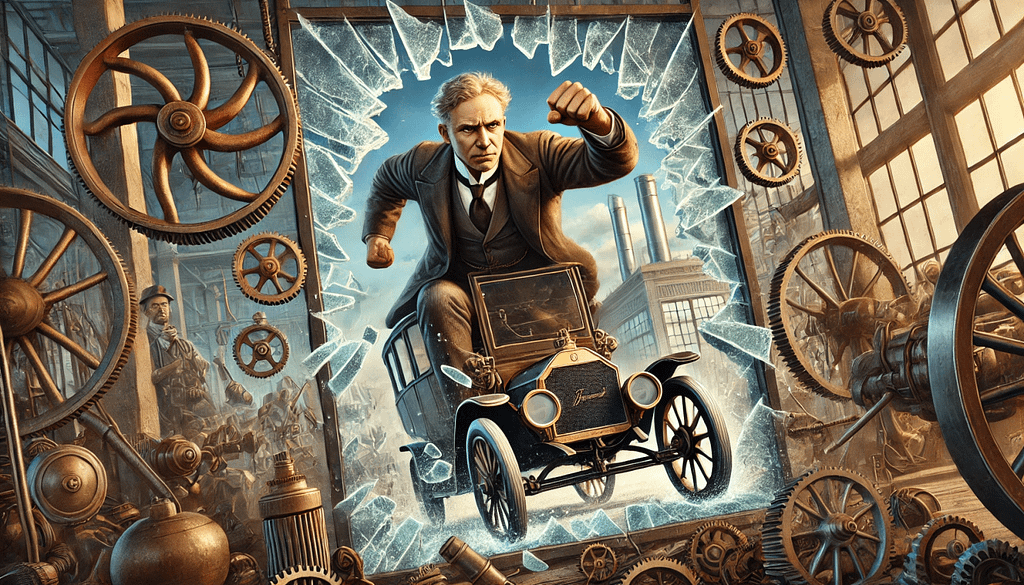

Ford Pulverises a Paradigm

“The horse is here to stay, but the automobile is only a novelty — a fad” — President of the Michigan Savings Bank

Imagine you live in the late 1890s. Most people travel by horse-drawn coach, railway, and streetcar. Rail is more comfortable than horse and cart because roads are glorified dirt tracks and suspension is not yet widespread. When you hear rumours of this thing called a motorcar, “a mechanical horse”, you dismiss it as a passing craze. After a while, you see several motorcars appear. These first cars are unreliable, need a lot of maintenance, and smell so badly that people call them “stink chariots”. Besides all that, there are no roads on which to drive stink chariots.

This is a flavour of the environment in which Henry Ford pursued his vision of a high-quality car at an affordable price. Many obstacles stood in the way of that vision, including trust in cars, the transport ecosystem, and even securing investment in his company.

Eventually, Ford revolutionised the automotive industry by introducing the moving assembly line, drastically reducing production costs and making cars affordable for the average American. This innovation drove a new paradigm of mass production and consumerism, fundamentally changing the manufacturing landscape and setting the stage for modern industrial practices. Ford’s Model T became a symbol of this transformation, embodying efficiency, standardisation, and accessibility.

The Balance Between Exploit and Explore

The Tightrope of Explore and Exploit

As with an organisation, over time, its strengths shift from its resources to its processes, guided by its business model. As teams effectively collaborate on recurring tasks, processes become more streamlined, entrenched, efficient, and well-defined. The business model shapes priorities, clarifying which activities are most critical. This evolution ensures that the organisation remains focused and efficient in its core operations. This efficiency comes at the cost of inflexibility, and innovation foots the bill.

Ford’s River Rouge plant was renowned for owning and managing the entire car-making process. The plant embodied the height of efficiency and vertical integration. Ford controlled raw materials from their source: iron mines, limestone quarries, coal mines, rubber plantations, and even forests. The company owned a fleet of barges and a railroad to ship materials from its mines to its plant, where iron ore, limestone, and coal were smelted into steel. Sand was brought in to make glass, and raw rubber to make tyres. Ford even had an on-site electrical power plant to supply the factory and its more than 100,000 workers. The goal was to own and control as many stages of production as possible, ensuring a seamless, efficient process from raw material to finished automobile.

Ford’s commitment to a highly optimised process turned the River Rouge plant into a well-oiled, efficient machine, a remarkable rut, but a rut nonetheless. For over a decade, the plant produced the Model T with only one significant incremental change: the removal of an unnecessary water pump. This focus on exploitation came at a cost. When engineers presented Ford with a prototype of an updated version, his response was to smash it to pieces with a sledgehammer and walk out without saying a word. This act symbolised Ford’s rigid adherence to a singular vision, stifling flexibility and innovation.

A period of incremental change based on the Model T design lasted until 1919 when General Motors introduced a radically new concept: the fully enclosed steel automobile. Within a few years, this innovation became the industry standard. In response, Ford temporarily shut down his famous River Rouge production facility to retool it for the new design. Ford’s single-minded attention to incremental change and increased productivity had stunted his ability to imitate General Motors’ innovation quickly.

This example illustrates a broader lesson: over time, an organisation’s capabilities shift primarily from its resources toward its processes, with the business model determining what it must prioritise. As teams successfully address recurrent tasks, processes become refined, defined, and entrenched. As the business model takes shape and clarifies which activities need the highest importance, priorities coalesce. However, an overemphasis on efficiency at the expense of innovation can render even the most well-oiled machines obsolete. Most incumbents like Ford may be prepared to dabble, to believe they are innovating. However, they are merely making small investments that won’t cannibalise what they have already created, nor distract them from that singularity of focus.

The Mental Model Challenge

“You Cannot Change Business Models Until You Also Change Mental Models” — Undisruptable (on a limited time deal on Amazon: https://amzn.eu/d/0a5NAUgK)

Behind this adherence to a business model is the more stubborn “mental model challenge”. Mental models serve as frameworks for intuitive judgment and proxies for rigorous analysis, filtering information, recognising patterns, making value judgments, and forging chains of causality.

However, the formation of shared mental models can become a liability when the strategic assumptions underlying them begin to deteriorate. As companies grow, their assumptions about competitors, customers, and sources of advantage can become outdated, leading to strategic missteps. While helpful, mental models can eventually become ruts.

Ford’s story serves as a cautionary tale for modern managers. Efficiency is important, but without a culture of continuous innovation and adaptability (Permanent Reinvention), even the most optimised processes can become a hindrance rather than a help. To avoid this trap, organisations must strike a balance between efficiency and innovation, exploitation and exploration, ensuring they remain resilient and responsive in an ever-changing business landscape.

Ironically, Henry Ford is purported to have said, “If you always do what you’ve always done you’ll always get what you’ve always got”. So if we want new results, we need to change our behaviour which means changing our routines which means changing all the little prompts that cause them and this means changing lots of other little things. Yet Ford too, got stuck in his ways.

If you work for a successful entrepreneur, even more so in the case of a successful family business, you know what I am talking about!

Thanks for Reading

For more on Ruts and The Tightrope of Exploit and Explore, check out our latest series with Wendy K. Smith, now also available on Spotify Video.

https://medium.com/media/559c4f34f6bd5a43e0cedf7a42dc1331/href

Prisoner of a Paradigm: Ford’s Rigid Rut was originally published in The Thursday Thought on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

The post Prisoner of a Paradigm: Ford’s Rigid Rut appeared first on The Innovation Show.