For Paid Substack Subscribers, we have a live session coming soon with Tony Ulwick, a pioneer of the Jobs-to-be-Done Theory and the inventor of Outcome-Driven Innovation® (ODI), a powerful strategy and innovation process with a documented success rate that is 5-times the industry average. Tony will join us in a small group and answer any questions you may have. I will be in touch with the date.

You can download a FREE copy of his ebook or audiobook here:

Jobs-to-be-Done Book | FREE PDF | Ulwick | JTBD Framework

“To know and not to do is not yet to know.” — Xunzi, Chinese philosopher

(Knowing without taking action does not equate to true understanding.)

In the quiet mining village of Aberfan, South Wales, on the morning of 21 October 1966, a tragedy unfolded that would resonate for decades. Perched precariously on the mountain slopes above the village, was a massive pile of mining waste. Heavy rains had saturated the area, causing water to accumulate within the tip, which was unfortunately above a natural spring. This combination transformed the waste into a deadly slurry.

At just after nine o’clock, the saturated hillside suddenly gave way. Half a million tonnes of debris surged downhill, engulfing Pantglas Junior School and a row of houses. The village descended into chaos in mere moments. Parents and police rushed to the scene, desperately trying to dig through the rubble. Despite their frantic efforts, a ten-metre-deep mass of slurry swallowed classrooms, resulting in the tragic loss of 116 children and 28 adults’ lives.

The leader of the National Coal Board (NCB) Lord Robens arrived in Aberfan. After visiting the disaster site, he gave a press conference at which he stated the NCB would work with any public inquiry. In an interview with The Observer, Robens said the organisation “will not seek to hide behind any legal loophole or make any legal quibble about responsibility”.

The following morning, a television news team interviewed Robens while examining the tip. When asked about the responsibility of the NCB for the slide, he answered, “I wouldn’t have thought myself that anybody would know that there was a spring deep in the heart of a mountain, any more than I can tell you there is one under our feet where we are now. If you are asking me did any of my people on the spot know that there was this spring water, then the answer is, No — they couldn’t possibly. … It was impossible to know that there was a spring in the heart of this tip which was turning the centre of the mountain into sludge.”

Despite his claims of ignorance, an official inquiry placed the blame squarely on the National Coal Board (NCB) and nine of its employees. The inquiry’s findings laid bare the NCB’s culpability, but the lack of legal consequences for those responsible added a bitter note to the community’s grief.

To add insult to the devastating injury, there had been many warnings. For several years before the disaster, local authorities had expressed major concerns about the risk of placing large amounts of mining debris on the hillside. Those running the mine consistently ignored these worries. Recorded correspondence from the time establishes the extent of these concerns.

For example, three years before the disaster, the Borough Engineer wrote to the authorities noting, “I regard [the situation] as extremely serious as the slurry is so fluid and the gradient so steep that it could not possibly stay in position in the wintertime or during periods of heavy rain,” and later added, “this apprehension is also in the minds of the residents in this area as they have previously experienced, during periods of heavy rain, the movement of the slurry to the danger and detriment of people and property.”

The Aberfan disaster remains a stark reminder of the dangers of ignored warnings and the devastating human cost of corporate negligence.

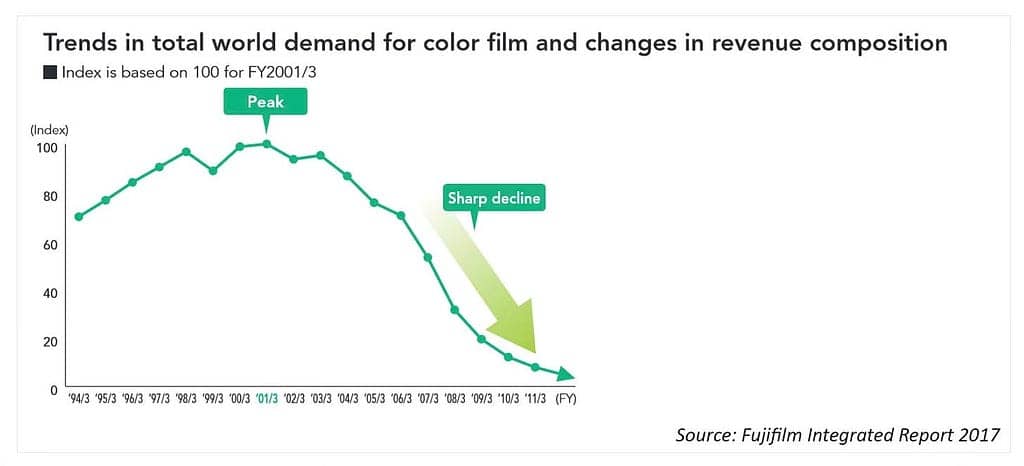

The Fujifilm vs Kodak Narrative in Ignored Warnings and Adaptation

Kodak, once a giant in the photography industry, failed to act on the knowledge that digital photography would soon replace film, leading to its bankruptcy in 2012. In stark contrast, Fujifilm recognised the impending threat of digital technology early and took decisive action to reinvent itself. In the year 2000, photographic products accounted for 60% of Fujifilm’s sales and 70% of its profit. Within a decade, digital cameras had devastated this business. However, unlike Kodak, Fujifilm continues to thrive. How did Fujifilm succeed where so many others failed?

Shigetaka Komori became CEO at Fujifilm’s most vulnerable point. After multiple rounds of cost-cutting, plant closures, and redundancies, Komori realised that merely trimming costs would not secure the company’s future. Instead, Fujifilm chose an undisruptable route through reinvention. They unbundled their capabilities, including patents in chemical compounds and nanotechnology, and systematically applied these in novel ways. As a result, Fujifilm now enjoys successful interests in healthcare, life sciences, pharmaceuticals, regenerative medicine, and even a COVID-19 vaccine. Although they still maintain a small footprint in areas related to their legacy products, such as digital cameras and instant photo systems, these account for only minor revenues.

FujiFilm Reinvention

Fujifilm’s entry into the beauty industry is an unequivocal demonstration of reinvention, using capabilities in new ways. On the surface, beauty products seem unrelated to photography, but (ahem) looks can be deceiving. Collagen, a key ingredient in camera film, is also crucial in beauty and healthcare products. Using their experience, entire departments that once focused on film products transitioned to developing beauty products. In 2007, Fujifilm launched a high-end skincare range called ASTALIFT, aiming to deliver “Photogenic Beauty” to its customers. Long before Kodak filed for bankruptcy, Fujifilm was already enjoying diversified annual revenues of over $20 billion, with only a minor contribution from photographic products.

The foundation laid by his predecessor, Minoru Ohnishi, who foresaw the need for transformation made Komori’s significant achievement possible. During the 1970s, a tenfold increase in the price of silver, essential for photo processing, shook the industry. While Kodak and others returned to business as usual after prices fell, Ohnishi saw this as a warning. He prepared Fujifilm for a radical shift, convinced that digital technology would revolutionise photography. Fujifilm began building diverse digital capabilities, and by 2003, it had nearly 5,000 mini digital processing labs in the U.S., compared to Kodak’s fewer than 100. This commitment to future-proofing the company set the stage for its later successes.

Fujifilm’s success story teaches us the importance of recognising and acting on warning signs. We can achieve remarkable results by actively assessing resources and remaining open to new opportunities. This approach, coupled with a willingness to accept failure, was crucial to Fujifilm’s transformation.

Fujifilm’s ability to repurpose its expertise and technology to adjacent industries, such as high-definition imaging and pharmaceuticals, showcases the value of heeding warnings and adapting to change. In contrast, Kodak’s failure to act on similar knowledge led to its downfall.

This stark contrast between Kodak and Fujifilm highlights the critical importance of heeding warning signs and adapting to change.

For regular followers of the Thursday Thought, you will know I am a collector of quotes. When I consulted my collection, I felt this one by C. S. Lewis is eerily accurate for the theme and opening anecdote of this article:

“The safest road to Hell is the gradual one. The gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without milestones, without signposts.”

Rather than leave you with a quote, I leave you with a question:

How do you ensure you are taking meaningful action on the knowledge you possess, rather than simply being aware of it? Not just in business, but in your relationships, your health, your career?

More articles like this:

Thanks for Reading

The latest episode of the show is an impromptu one while I was at a board meeting on Clare Island in Ireland.

https://medium.com/media/26086729ffdc85745f3b676aad004127/href

Knowledge Without Action: Aprés Moi Le Déluge? was originally published in The Thursday Thought on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

The post Knowledge Without Action: Aprés Moi Le Déluge? appeared first on The Innovation Show.