“Once a detective decides that he or she has found the killer, the confirmation bias sees to it that the prime suspect becomes the only suspect. And once that happens. an innocent defendant is on the ropes… Doubt is not the enemy of justice; overconfidence is…True scientists speak in the careful language of probability.” — Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson

In 1980, Thomas Lee Goldstein, a college student and ex-Marine, was wrongfully convicted of a murder he did not commit. Goldstein spent 24 years in prison. There was no physical evidence against him: no gun, fingerprints, blood, or motive. His conviction relied solely on the testimony of jailhouse informant Edward Fink and an unreliable eyewitness.

Fink, a heroin addict with a criminal history, was notorious for testifying in multiple cases where defendants supposedly confessed to him. Described as “a con man who tends to handle the facts as if they were elastic,” Fink lied under oath about receiving a reduced sentence for his testimony. The only other support came from Loran Campbell, who identified Goldstein after police falsely claimed he failed a lie-detector test. Four other eyewitnesses described the killer as “black or Mexican,” while Goldstein is white. Furthermore, Campbell later recanted, admitting he was overly eager to assist the police.

Despite 5 judges agreeing that prosecutors had denied Goldstein a fair trial, Goldstein remained imprisoned until 2004, when a California Superior Court judge dismissed the case, citing its reliance on perjured testimony. Nevertheless, the Los Angeles District Attorney’s office promptly filed new charges and set bail at $1 million. Deputy District Attorney Patrick Connolly maintained, “I am very confident we have the right guy.” Two months later, they conceded they had no case and released Goldstein.

Social psychologist Richard Ofshe compared convicting the wrong person to a physician amputating the wrong arm (it happens). If faced with evidence of such a grave error, one’s first impulse is to deny it to protect their job, reputation, and colleagues. In the case of amputating the wrong limb, some physicians have placed the responsibility on the patient!

Cognitive dissonance compels us to rationalise our actions and decisions, even in the face of clear contradictory evidence. The more time and effort we invest in an initial decision, the greater the dissonance we experience.

Once we have made a decision, we resist information that casts doubt on that decision. This psychological phenomenon also manifests in other fields, such as business, where leaders often continue poor investments due to commitment bias, also known as the escalation of commitment. They stick with decisions long past their usefulness to appear consistent and avoid the uncomfortable realisation of being wrong.

Once we have placed our bets, we don’t want to entertain any information that casts doubt on that decision.

There’s an old adage, “There is no such thing as a good investment in a bad business.” Although many leaders recognise this truth, it is only in the heat of the moment that they succumb to the hypnotic influence of confirmation bias, commitment bias and cognitive dissonance. This was the case when the U.S. tyre industry was flipped on its head with the threat of a new technology, the radial tyre — a change incumbents denied for decades.

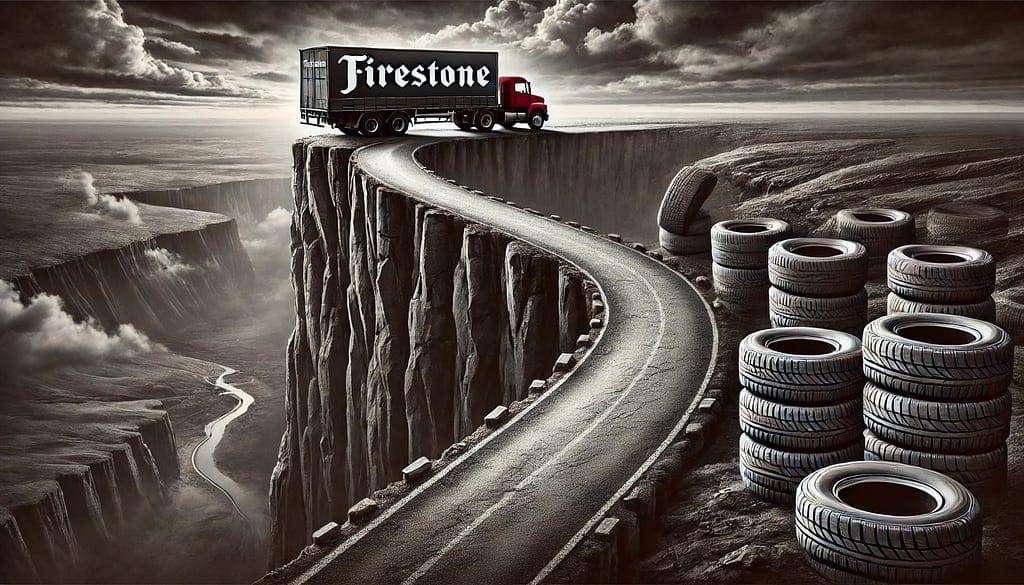

Down the Wrong Road — The Bias of The Bias (Tyre)

“No matter how far you have gone on a wrong road, turn back.” — Turkish proverb

In the 1960s, Firestone enjoyed 25% of the domestic tyre market in the US. The top five domestic tyre firms — Goodyear, Firestone, B. F. Goodrich, Uniroyal, and General Tire — together accounted for over 80% of industry capacity and shipments and captured nearly all the growth in volume over this period. Between 1960 and 1972, these five companies responded to increased demand by building eighteen new domestic tyre plants. By 1988, Firestone had been acquired by Japanese competitor Bridgestone, and only Goodyear, one of the five biggest U.S. tyre firms, remained independent. What happened?

Just as Nokia and RIM (Blackberry) knew about changing customer demands, the rise of the iPhone, and the advent of the Internet, they chose to focus on their existing products, capabilities, and business and mental models. In the case of Nokia, like the tyre factories, to exploit their current advantage and drive down costs, they invested in dumbphone factories in China. They not only knew about the rise of the smartphone, they mocked it and just hoped it would diffuse with a trickle, not a tsunami. Despite trying to stem the flood, like the Dutch boy with his finger in the dam, they eventually met their demise.

For Firestone et al, the new technology was the radial tyre. Radial tyres lasted twice as long as the US-dominant bias tyre technology. Even more damning for the bias tyre, radial tyres increased fuel efficiency, handling, and safety.

French tyre maker Michelin pioneered the radial tyre and grew its market share throughout Western Europe. Buoyed by this success, Michelin turned began inroads into the US market. Michelin, which contracted with Sears to manufacture radial tyres under the Allstate label, announced its intention to build a $100 million radial tyre factory in North America. Domestic rival B. F. Goodrich introduced domestically produced radials as an opportunity to gain market share from larger rivals Firestone and Goodyear. Radials were en route.

As is the case with cognitive dissonance, the US incumbents sneered at and mocked the radial tyre, dismissing it at first, just as Nokia and RIM did with the iPhone.

To satisfice customer demand and dampen the adoption of radial tyres, Firestone and Goodyear responded by introducing a slightly modified version of the traditional tyre. Goodyear introduced the “belted-bias” tyre in 1967 and Firestone followed the same road a few months later. This was a classic case of cramming a new technology into existing capabilities (i.e., trying to adapt old methods and infrastructure to accommodate new advancements without fully embracing the new technology).

While the tyre companies were aware of General Motors and Ford’s interest in radial tyres, they had hoped for a gradual diffusion. When both GM and Ford announced their intention to place radial tyres on all models over the coming years, the incumbent tyre manufacturers were left with no choice but to comply.

As case after case of disruption exposes, the more systemic a change needs to be, the more time that is needed for a company to adapt. Many companies, like Firestone, will live with the cognitive dissonance of business as usual in the face of a need to transform.

Firestone’s response to the radial tyre was shaped by cognitive dissonance and its entrenched bias towards bias tyre capabilities. First, the company introduced the belted-bias tyre, leveraging existing factories and skill sets. This required only minor modifications to production equipment and modest capital spending in 1968 and 1969. Second, to meet automakers’ demands and compete with Michelin, Firestone decided to manufacture radials using modified bias tyre equipment. This allowed for rapid production increases but likely contributed to quality problems. The reliance on familiar methods and infrastructure reflects the company’s reluctance to fully embrace new technology, illustrating cognitive dissonance in its strategic decisions.

Take The Road Less Travelled

The downfall of Firestone and the wrongful conviction of Thomas Lee Goldstein both serve as stark reminders of the perils of cognitive dissonance and commitment bias. All of us, whether in business, law, or life, must remain vigilant against the seductive comfort of entrenched beliefs and practices. The refusal to adapt and acknowledge mistakes can lead to catastrophic failures, be it the collapse of a business empire or the destruction of an innocent life. The road to failure is paved with overconfidence and resistance to change; only by recognising and combating these biases can we steer towards a future of innovation, justice, and success. The road less travelled is often the road to breakthrough.

Thanks for Reading

For more on Firestone, we will host Joseph Bower in a series in late 2024, or early 2025. We also intend to host Richard Tedlow.

For more on cognitive dissonance, check out our latest episode with Carol Tavris, co-author of “Mistakes Were Made But Not By Me”.

https://medium.com/media/671a40844ebddc2ff7940ca51593210d/href

From Bias Tyres to Biased Minds: The Road to Firestone’s Failure was originally published in The Thursday Thought on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

The post From Bias Tyres to Biased Minds: The Road to Firestone’s Failure appeared first on The Innovation Show.