“Worldly wisdom teaches that it is better for reputation to fail conventionally than to succeed unconventionally.” — John Maynard Keynes.

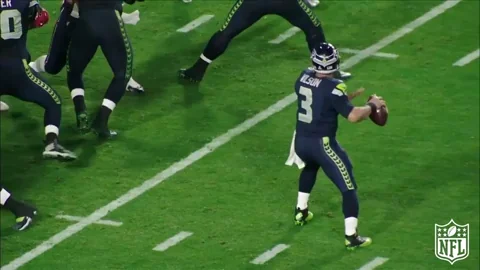

In the dying moments of Super Bowl XLIX, a coaching decision became one of the most debated in football history. With just 26 seconds left on the clock and the Seattle Seahawks down by four points at the New England Patriots’ one-yard line, Coach Pete Carroll made a daring call. Instead of handing the ball to his star running back, Marshawn Lynch, he called for a pass. The result was disastrous — an interception that sealed the Patriots’ victory. Critics quickly labelled it “the dumbest play in history.”But was it truly a terrible decision? Or was it a calculated risk that simply fell victim to bad luck?

This moment in sports exemplifies a broader issue seen across many organisations today: the tendency to play it safe rather than embrace unconventional strategies that might lead to greater success. Carroll based his decision on sound logic, even though it was controversial. The element of surprise could have caught the Patriots off guard, leading to a game-winning touchdown. But in the aftermath of failure, it was easier for critics to denounce the decision rather than understand its rationale. It takes substantial and sustained intellectual energy to develop innovative strategies rather than to follow common logic. Such capacity to devise new strategies or reinvent old ones is a prerequisite for winning, whether you are a sports team or an executive team.

Economist Professor David Romer sheds light on this phenomenon through his analysis of NFL punt data from 1998 to 2004. Romer’s study revealed that NFL teams should avoid punting when facing a fourth down with less than four yards to go for a first down. Statistically, going for it was often the better option, yet many teams continued to punt. Why? Because punting was the conventional wisdom. It was the safe choice, the one that wouldn’t draw ire if things went wrong.

Despite Romer’s findings, which clearly showed that punting was frequently the wrong decision, most NFL teams reverted to what they knew best. Some experimented with the unconventional approach, but the pressure to conform, to avoid criticism, drove them back to the traditional playbook.

Countless organisations mirror this scenario. Leaders often face choices that pit innovation against tradition and risk against convention. The fear of unconventional failure can be so overpowering that it stifles the potential for unconventional success. Organisations cling to familiar strategies, even when evidence suggests a better way, because the perceived safety of the status quo offers comfort, even at the cost of potential growth.

To the untrained eye, Seahawks Coach Pete Carroll’s decision during Super Bowl 49 to call for a pass instead of a run might seem like a catastrophic mistake, but when examined through the lens of sound decision-making, it was far from a radical call. As Annie Duke highlights on the latest episode of The Innovation Show, Carroll was navigating a complex scenario with 20 seconds left, trailing by four points, with only one timeout remaining.

Carroll had two general options: run or pass. Each choice led to multiple outcomes.

Running the ball could result in:

(a) A touchdown, securing an immediate win.

(b) A turnover by fumble, leading to an immediate loss.

© The runner being tackled short of the goal line.

(d) An offensive penalty.

(e) A defensive penalty.

Seattle would need to use their final timeout if the runner got tackled short. If they didn’t score on the next run, time would likely expire, ending the game.

Passing the ball could result in:

(a) A touchdown, leading to immediate success.

(b) An interception, resulting in immediate failure.

© An incomplete pass.

(d) A sack.

(e) An offensive penalty.

(f) A defensive penalty.

The key difference between these options is that passing would likely allow Seattle three chances to score instead of just two if they ran the ball. An incomplete pass would stop the clock, leaving time for additional plays, while an interception — a low-probability event at 2%-3% — would end the game. The marginal increase in risk from an interception was a small price to pay for the strategic advantage of having three potential scoring opportunities instead of two.

Carroll’s decision, viewed through this detailed scenario analysis, was not as unconventional as it seemed. It was a calculated risk, balancing the probabilities and potential outcomes, making it a sound move under the pressure of the game’s ultimate moments. (Interestingly, the winning Patriots coach Bill Belichick also made a calculated decision not to call a timeout before the interception, after seeing Seattle’s personnel grouping. He explained that allowing the clock to run while positioning his defence gave them the best chance to stop a potential running play).

Despite this logic, ten years later, people still call Carroll an idiot. The fans were mad. The pundits were mad. But those with inside knowledge, such as Belichick understood that Carroll made a sound decision. The real shame is, from an innovation perspective that If he handed the ball to Marshawn Lynch and lost, no one would have cared, because that’s what everyone expected. And therein lies the real dilemma — innovation invites greater risk, not necessarily in the outcome, but in the perception of the outcome!

This is where Carroll’s situation mirrors the bind that leaders face in established organisations today. Had Carroll done the expected thing — running the ball — and lost, it would have been seen as “bad luck” rather than a failure. But because he chose the unexpected, the innovative option, and it didn’t work, he was labelled a fool.

“One of the things that I think is really tragic is that enterprises are (already) de-risked. They have so many resources and yet they aren’t really willing to take these bets. The innovator’s dilemma, right? And that I think is a real shame because they’re the most de-risked of all. And yet you really don’t see a lot of innovation coming out of enterprise situations.” — Annie Duke, Innovation Show, EP 547

On this week’s episode of The Innovation Show, Annie Duke highlighted how the judgment of failure differs drastically between startups and mature organisations. In the startup world, entrepreneurs almost expect failure, which gives them the freedom to explore, innovate, and take risks without the fear of significant repercussions. This leniency fosters a culture of experimentation and learning. You learn your way towards success. As we say in the sports world; “I don’t lose, I win or I learn.”

“You can choose courage, or you can choose comfort, but you cannot choose both.” — Brene Brown

In contrast, failure in a mature organisation can be career-limiting, if not outright career-ending. This harsh judgment creates a culture of massive risk aversion. Leaders in established companies may avoid innovative decisions, not because they lack the insight or the data to support a bold move, but because the consequences of failure are so severe. The stakes are higher, so the inclination to “play it safe” becomes the default, stifling potential breakthroughs and limiting future organisational growth.

Many heads of Innovation/Transformation/ESG mistakenly believe(d) that they have (or had) air cover from senior leadership. They assume they have protection, but in reality, they are more akin to canaries in coal mines, actors in a social experiment. (To ensure this doesn’t happen to you check out our series with Peter Compo on strategy and our Corporate Explorer Series, thanks to our friends at Wazoku links to both are below.)

Should they win, the credit belongs to leadership.

Should they lose, the failure belongs solely to them (and they discover just how lonely the coal mine truly is.)

Peter Drucker once said, “People who don’t take risks generally make about two big mistakes a year. People who do take risks generally make about two big mistakes a year.” This insight reminds us that mistakes are inevitable, regardless of the path we choose.

However, the difference lies in the potential rewards. Playing it safe may shield us from scrutiny, but it also prevents us from achieving greatness. Taking calculated risks, however, opens the door to innovation and extraordinary success.

Find that episode with Annie Duke here:

https://medium.com/media/02fb6e86f5afc673b02059e29f54d79d/href

Charles Conn here:

https://medium.com/media/24980349501afea5e8d93e40c079da86/href

Peter Compo series here:

https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLMxiNrgE29RK-rijxNMQpdi26oSo9erAq&si=Mr1TV4oBpDPg1iDa

The Corporate Explorer Series:

https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLMxiNrgE29RLfbN-61eiZcoxPneZS-4qg&si=DHFYvwIpdZchicDv

Find Annie:

Substack:

https://annieduke.substack.com/

Find Aidan:

Better for Reputation to Fail Conventionally was originally published in The Thursday Thought on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

The post Better for Reputation to Fail Conventionally appeared first on The Innovation Show.