“We can not solve our problems with the same level of thinking that created them” — Albert Einstein

“Do not repeat the tactics which have gained you one victory, but let your methods be regulated by the infinite variety of circumstances.” — Sun Tzu

“The righter we do the wrong thing, the wronger we become. When we make a mistake doing the wrong thing and correct it, we become wronger. When we make a mistake doing the right thing and correct it, we become righter. Therefore, it is better to do the right thing wrong than the wrong thing right. This is very significant because almost every problem confronting our society is a result of the fact that our public policymakers are doing the wrong things and are trying to do them righter.” — Russell Ackoff

In his stand-up show called “Nursery Rhymes”, comedian Ricky Gervais probes for the morals (or lack thereof) in popular nursery rhymes. He admits that a moral in “Humpty Dumpty” eludes him. As a quick reminder, it reads as follows.

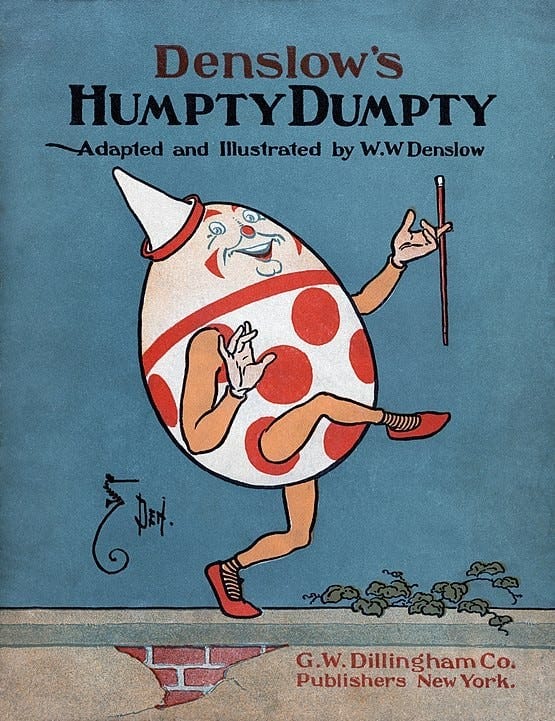

Cover of a 1904 adaptation of Humpty Dumpty by William Wallace Denslow.

“Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall,

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall.

All the king’s horses and all the king’s men

Couldn’t put Humpty together again.”

Grasping for an underlying message in the rhyme, Gervais extrapolated, “Don’t send horses to perform medical procedures. Of course, they couldn’t put him together again. They haven’t got the dexterity. They can’t even scrub up! They haven’t got thumbs, never mind opposable thumbs! They couldn’t sew to save their life. If I had to design their perfect egg-crushing device, it would be a hoof.”

The Einstellung Effect

“Eventually, your tools will end up limiting you.” — Eric Von Hippel

The “Einstellung effect” is a cognitive bias that can significantly affect business leaders, making it harder for them to make the best decisions. It happens because we tend to stick too much to what we already know when we have limited tools or strategies. This bias is a fixed mindset or problem-solving approach in individuals and organisations. We use familiar strategies, even when they no longer work well for a particular situation. This leads to missed opportunities, distorted perceptions of reality, inefficiencies, and difficulty adapting to changing market conditions. Like all biases, the challenge is that we’re unaware of it.

“Even though most managers don’t think of themselves as being theory driven, they are in reality voracious consumers of theory. Every time managers make plans or take action, it is based on a mental model in the back of their heads that leads them to believe that the action being taken will lead to the desired result. The problem is that managers are rarely aware of the theories they are using — and they often use the wrong theories for the situation they are in. It is the absence of conscious, trustworthy theories of cause and effect that makes success in building new businesses seem random.” — Clayton Christensen

One persistent issue when evaluating new ideas is the way we measure them. In a recent episode of The Clayton Christensen tribute series, Derek van Bever, co-author of “The Capitalist’s Dilemma,” explained how companies, based on their measurement criteria, often choose to leave a low-end market and move upstream. According to their measurement tools, the low-end opportunity seems like a waste of company resources, so they exit. However, once they do, a hungry newcomer or low-end competitor quietly takes advantage of the leftovers, which grow more valuable over time. These initially overlooked newcomers eventually build the capabilities to move upstream and compete with the established companies. Management teams overlook these opportunities because they use the wrong tools, such as outdated competitive metrics and rigid financial goals. When companies rely on obsolete performance metrics, they fail to see when they’re in trouble.

Success Pictures

The case of AMR, the parent company of American Airlines, provides an interesting example. They were pioneers in using data for yield management in the airline industry since the 1950s. They even partnered with IBM to create a cutting-edge data processing system called SABRE. However, as new, cost-efficient competitors emerged in the late 1970s, AMR continued to compete with traditional airlines, overlooking the significantly different cost structures of the newcomers. The CEO, Robert Crandall, saw these competitors as temporary and focused on maximising revenue based on the old cost structures (old tools). This approach, developed over three decades, made it hard for them to adapt to the new competitive landscape. As Abraham Maslow said, “If the only tool you have is a hammer, you tend to see every problem as a nail.”

Consider the case of AT&T’s failure to recognise the potential of the mobile phone revolution. In 1980, AT&T, whose Bell Labs had invented cellular telephony, sought the expertise of a renowned consulting firm to forecast cell phone penetration in the U.S. by 2000. The consultants’ prediction projected a mere 900,000 subscribers, which accounted for less than 1% of the eventual figure of 109 million. Guided by the research, AT&T concluded that the market would not justify the investment.

At that time, the prevailing data available to AT&T painted a discouraging picture of the mobile phone landscape. These devices were cumbersome, bulky, and expensive, making them inaccessible to most people. Using their evaluation tools, it seemed rational for AT&T not to allocate resources towards a limited opportunity. This decision by AT&T exemplifies the Einstellung effect, wherein the company relied on their familiar metrics (tools) to forecast the potential. When you introduce any metric, you introduce new constraints.

Firms require the right tools and strategy to understand how to introduce innovations. This points to what Christensen and van Bever call the capitalist’s dilemma: Doing the right thing for long-term prosperity is wrong for most investors, according to the tools used to guide most investments. In a previous Thursday Thought, I wrote about how organisations become “Captive to Customers”. Equally, specific performance metrics in an established domain often make little sense in an emerging one, and thus, leaders become tethered to the tools of their past.

Thanks For Reading. (For more of this content, sign up to our Substack here: https://thethursdaythought.substack.com).

Check out our friend Alexander Osterwalder and his Exploit-Explore Continuum for a modern measurement tool. This was a top-rated episode aired in January 2023.

https://medium.com/media/2d305c1769801c5793cdcffa3d6bec2e/href

The finale of our magnificent series with Paul Nunes is live; Paul speaks to many of the themes in this article.

It was a privilege to spend time with this man.

https://medium.com/media/2cdefc5968fed86b0d56fc79c1fc0d75/href

Old Tools: Tethered to Tools of the Past: The Humpty Dumpty Conundrum was originally published in The Thursday Thought on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

The post Old Tools: Tethered to Tools of the Past: The Humpty Dumpty Conundrum appeared first on The Innovation Show.